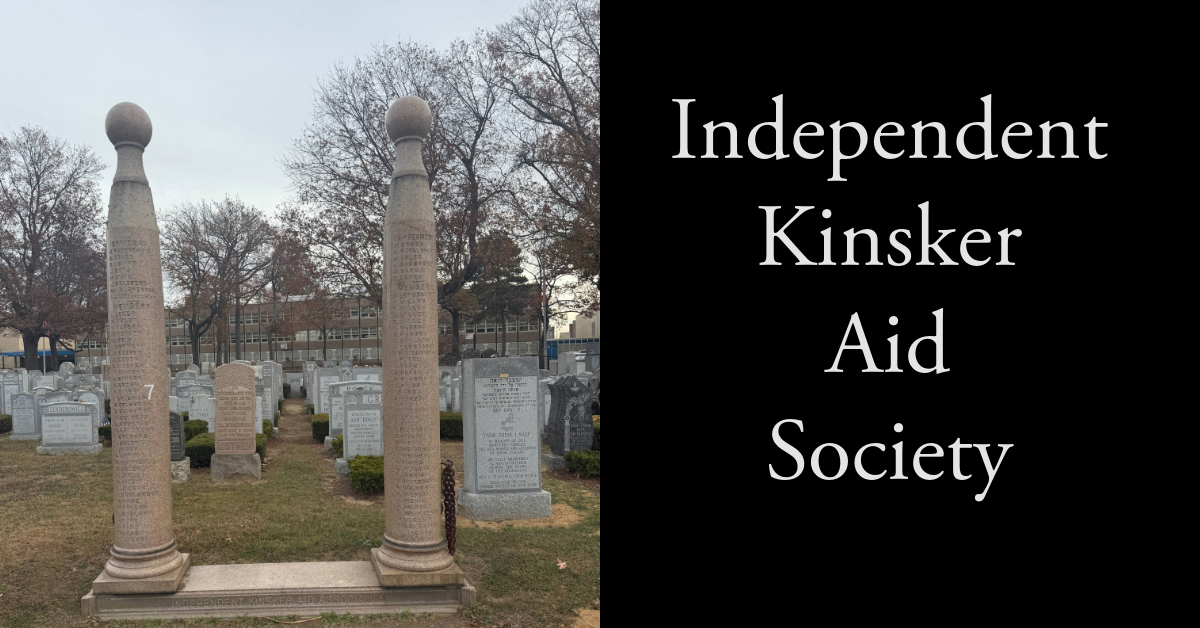

Independent Kinsker Aid Association

The Independent Kinsker Aid Association was founded in New York in 1904 by immigrants from Konske, Poland. The society maintained a relief committee after World War II, which aided survivors who came to the U.S. The society also sent food packages to the landslayt in Israel.

Research has shown that initial Jewish presence in Konske began around the 16th century, when King Zygmunt III Waze allowed them to purchase foods and other goods in the town. These rights, in addition to the right to build houses, were cemented in 1635. The Jews of Konske worked in the areas of trade and craft, mainly as shoemakers, carpenters, tailors, cap makers and furriers. By 1865, the community had a wooden synagogue, a cheder, a mikvah, a cemetery, and a funeral home. Also, by this time, the Jewish population had grown to over 4,000 people. In September of 1931, it is recorded that there were approximately 6,500 Jews in Konske.

The Jewish community is largely credited for the economic development of Konske. Specifically, twenty-six of the thirty-four establishments were Jewish owned (i.e. cast iron & enamelled castings factory, agricultural machinery factory, soap factory). One such business, an iron casting factory (Słowianin) owned by Mojżesz Hochberg, would export its products regularly to Russia. Hochberg was also a social activist, and facilitated the establishment of a Jewish orphanage in Konske. In addition to this, other communal institutions were established throughout the 19th/20th centuries, such as additional cheders (totaling to four), an Orthodox school, a Yeshiva, and a girl’s school (Beit Yaakov). In 1932, the mikvah was renovated and the synagogue was modernized (refurbished with stone). Local commerce shops such as cloth stores (8), delicacy shops (4), taverns/restaurants (16), and grocery stores (82) were prominent throughout the town.

The Jews of Konske were also very engaged in the political wellbeing of their town and community. During the 19th/20th centuries, Zionists groups began to be formed. Youth Zionists groups were also created. The Bund was organized around 1905, and its members participated in revolutionary acts such as strikes. The Bund maintained a soup kitchen, and had a cultural center, which allowed for lectures and performances to be held. In addition, a number of organizations were established by the artisans, merchants, tailors, and butchers of the community.

In September of 1939, Germans invaded Poland. Immediately, the social, political, and economic mobility of the Jewish population was severely restricted. Jewish businesses were either taken over or sold for low prices. The synagogue was destroyed by fire. A Judenrat was quickly established, with Józef Rosen appointed as the Head. On October 12, 1939, twenty-two Jews were killed. In February/March of 1941, Jews began to arrive from other Polish towns that had been incorporated into the Reich (Lodz, Sosnowiec, Kielce, Lopuszno, etc.). Shortly after, a ghetto was established (10,000 inhabitants) , surrounded by Strażacka, Trzecizgo Maja, and Warszawska Street from number 25 upwards. In November of 1942, the ghetto was liquidated. Aktzias (“Actions”) were carried out on November 3-4, November 7-9, and January 6-7 of 1943. Some inhabitants were transported to the Treblinka extermination camp (2000 killed). Those who survived the liquidation were transported to the Szydlowiec ghetto in January 1943. Today, there exists a plaque commemorating the death of the twenty-two Jews on the Main Square. The plaque allows for us to learn about and remember Konskies’ Jewish community. May their memories live on.

We would like to highlight a special resident of these grounds. A Holocaust survivor who shared her testimony throughout her life to educate others. We remember her fondly as she came to Mount Hebron to share her heroic life with us.

Francis Irwin was born in the spring of 1922 in Konske, Poland, which was a thriving Jewish community at the time. She was the fifth of seven children to generous and loving parents. However, Francis is the only survivor of her family. She attended public school and a yeshiva in the afternoons and had a normal early childhood. Francis recalls that there was antisemitic sentiment in Poland well before the Nazi invasion, usually in the form of boycotts of Jewish owned stores, which hurt the Irwin’s wholesale leather business.

Irwin had just graduated from elementary school when she learnt about Hitler. However, once the Nazis invaded Poland it would be impossible for her not to hear his name. In her memoir, Francis recalls Nazis’ brutal treatment from the get-go with absolute sadistic horrors, like mass graves and men being buried alive. Francis notes how the Holocaust began in stages. On the third day of their invasion, the Nazis burnt down the town’s Synagogue, which Francis describes as a huge loss when she poetically states that, “we felt like part of us was burning” when they watched the building ablaze. The Nazis began collecting all the Jews’ valuables and sending men to work. Her father had to hide in their walls to avoid being rounded up. If it was not enough to take their valuables and men, the Nazis then closed all Jewish businesses.

The next stage in the sadistic process was the ghettos. Francis recalled how the ghetto she was forced to live in was so cramped and packed that many people could not even lie down at night. They lived this way for one year. Because Francis’s Polish was the best in her family she was designated to sneak out and try to smuggle the bare necessities, like food, into the ghetto. After a year, the Jews of the Konske ghetto was told they would be “resettled”. Because of her amazing Polish, Francis’s father believed she would be the only who could survive if she fled and, therefore, told her to run from the ghetto and hide. The last thing he ever told her was to “remember to be a good human being”. Francis took this lesson with her throughout her life, as she said that the words are “always in my ear” and she even used it as the title of her memoir. Like many survivors struggling with the guilt for living, Francis felt extreme sadness for being the one designated to leave. She did not believe she had a chance to survive but left anyways to make her father happy.

She left the ghetto through the sewer and hid with some Jews in there for a few nights until they were found by the Poles. She then called on the help of some righteous gentiles, like her old teacher and the mayor of her town and his wife, who helped her obtain Polish papers. Francis did not want to endanger the couple, who could be punished for helping a Jew. Therefore, she ran to the woods where she survived off wild berries and raw potatoes and lived this way for a whole summer and half a winter. After, she went to Shidolevitz, where she lived with other Jews hiding in an abandoned factory. It was there that she learnt that her brother-in-law was alive in a Ghetto in Radom. She travelled with three girls around her age, and they snuck themselves into the ghetto on New Years Eve, when the Germans were drunk. However, her reunion with her brother-in-law was short lived because the Nazis found out about the interlopers and demanded they turn themselves in. The SS officers said that for every day they did not turn themselves in, they would kill ten Jews in the Ghetto. Not wanting innocent blood to be spilled, Francis gave herself over the Nazis.

The SS officers extensively interrogated the girls because they believed, falsely, that Francis and the others were revolutionaries. The interviews included brutal torture and beatings because the Nazis refused to believe that they were not affiliated with partisan groups. After the cruel torture, Francis and the three other girls were sent to Auschwitz and were told they were lucky there were not shot right then and there.

Francis argued that “you cannot describe the inhumane conditions of Auschwitz”. Upon arriving to the camp, Francis describes the horrible atrocities that took place there. She recalls seeing emaciated people that looked like the “walking dead”. She also recalls hearing classical music playing, which was a horrifying juxtaposition that symbolized the Nazi’s nonchalant attitude of murdering the innocent. She began to cry because of what she was witnessing, and an officer told her not to cry yet because it was just the beginning. Francis, along with the other new arrivals, were forced to strip off all their clothes, shower, and walk naked in the dead of a Polish winter.

The job she was given, after being chosen to live, was to collect scraps of metal outside the camp all day. One day an SS guard saw Francis straighten up for one moment and released dogs onto her with a big smile on his face. A dog bit her on her thigh and she was forced to clean it with dirty snow from the ground and continue working. The snow was blackened from the ashes of burnt bodies. After their long days of work, with only potato peel soup to eat, the SS officers would make the inmates stand in line for hours as they counted them. Every night they would go to sleep on crowded bunks made of wood and straw and every morning they would wake up to find a few who did not last the night. This horror was part of the routine as Francis states, “it was horrible, you couldn’t even cry, there were no tears.”

Francis attributes her survival to hope and faith that she would see her family again and the strong will to outlive Hitler and prove that he did not win. She viewed survival and hope as a form of protest. Despite all the terrible evil she witnessed and went through, Francis kept her faith in God and her fellow man, as she powerfully said, “I learnt about friendship in Auschwitz. When I was cold strangers shielded me with their bodies, for they had nothing to offer but themselves,” as many of her fellow inmates risked their lives to keep her alive. Francis also had another, more concrete, form of protest, when she was involved in exploding dynamite in one of the camp’s kitchens.

In January 1945, the Nazis informed the prisoners that they were leaving camp immediately, and the rumor circulating was that the Russians were close. They forced them on what is now known as a ‘death march’, subject them to walk in the brutal Eastern European winter for days on end, only stopping at nightfall. Whoever ceased walking was instantly shot and many did not survive. After the gruesome death march, which Francis barely survived, she was sent to Lenzing camp in Austria. It was there that American troops liberated her. She felt shocked when the soldiers began weeping at the sight of the survivors. She was so appreciative of her liberators and could not believe Americans came all that way to help her. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the JDC) sent the survivors packages and tried to aid them with all their needs.

After being liberated, she was immediately taken to an American makeshift hospital and was placed into a full body cast because the doctors feared she would break her bones if she moved, as she was that emaciated. Afterwards, she was in a displaced persons camp in Austria, where met her husband, Ruben. Strangers in the camp gave her away at the alter and that was when she realized how her new life would be, without family. Besides for her whole family being killed, she learnt that her entire town was sent to Treblinka and very few survived.

She moved to Flatbush, Brooklyn in the summer of 1947, and received a very warm welcome from the Jewish community there. Because she “grew up in Aushwitz”, she completed high school in Brooklyn as an adult. In 1949, she gave birth to her son, Martin, named for her father. When she learnt that the JDC, the organization that helped liberate her, received money from UJA, she became a very active member, as she felt a responsibility to show her gratitude and help them. She had a very extensive philanthropic resume, not only helping UJA but other organizations like the Hillel at Brooklyn College, as well. She also helped many Russian Jews who immigrated from the Soviet Union become acclimated into American society, because she remembered how hard her life was as an immigrant. She was very dedicated in investing and enriching Jewish communities, like she explained, “a united Jewish community is very important to me…a community dedicated to remembering a terrible past and hoping to build a better future. Together we can do everything, as individuals we are powerless.” Francis dedicated the rest of her life in charitable work and educating people on the Holocaust. She passed away in May 2015 in New York at the age of 93.

Despite all the evil and hatred, she faced, Francis Irwin never lost her faith in humanity. In fact, she chose to focus on the good that she could find in her others. Additionally, she heeded her father’s advice and was a good, caring person. Her extraordinary life, as a survivor, educator, and philanthropist are one that everyone can be inspired by.

https://swietokrzyskisztetl.pl/asp/en_start.asp?typ=14&menu=206&sub=173

https://konskie.travel/history_of_the_jewish_community_in_the_town_and_region_of_konskie

https://sztetl.org.pl/en/node/1041/116-sites-of-martyrdom/47117-ghetto-konskie

https://sztetl.org.pl/en/node/1041

https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol1_00240.html

~Blog by Olivia Scanlon