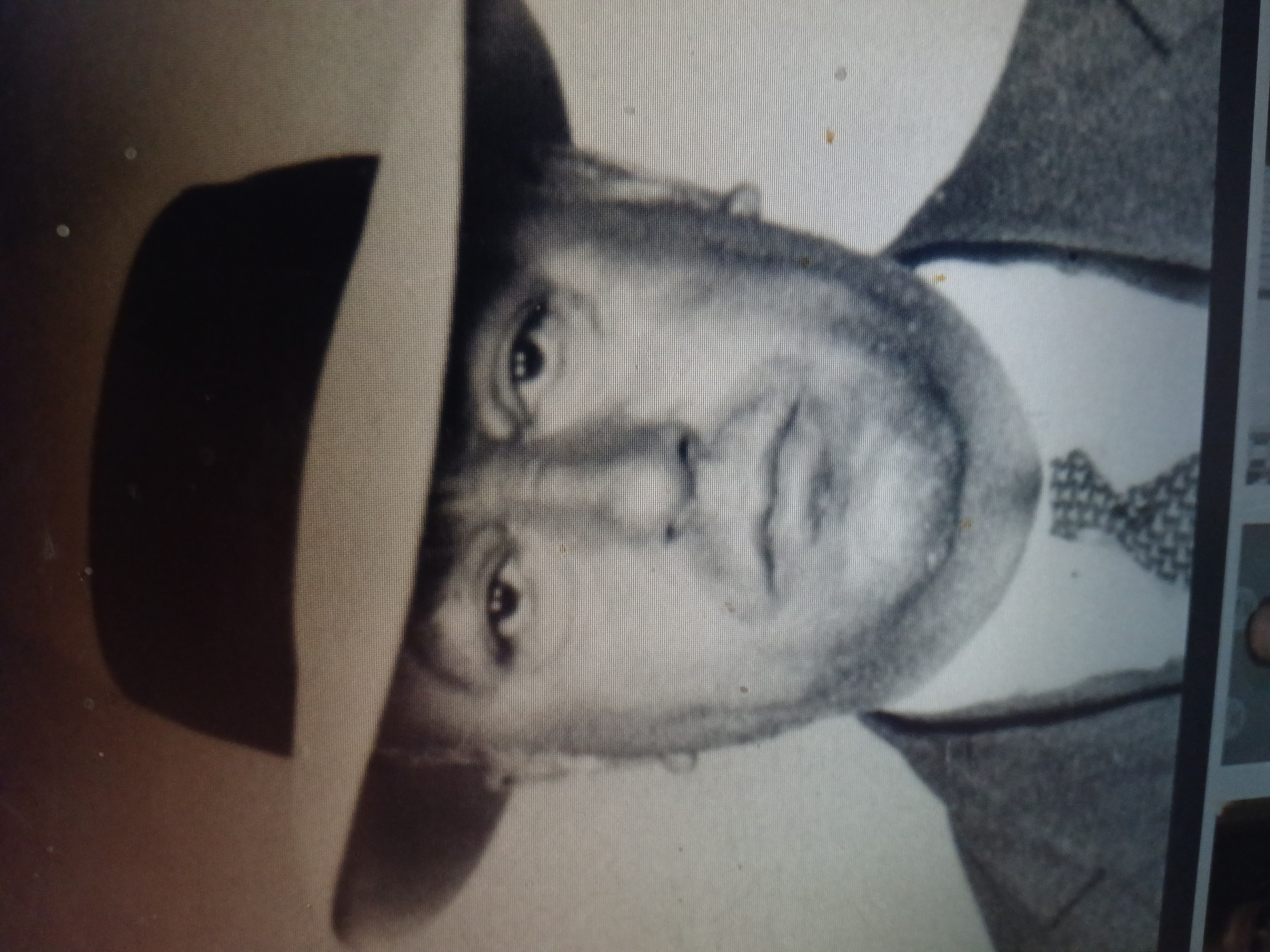

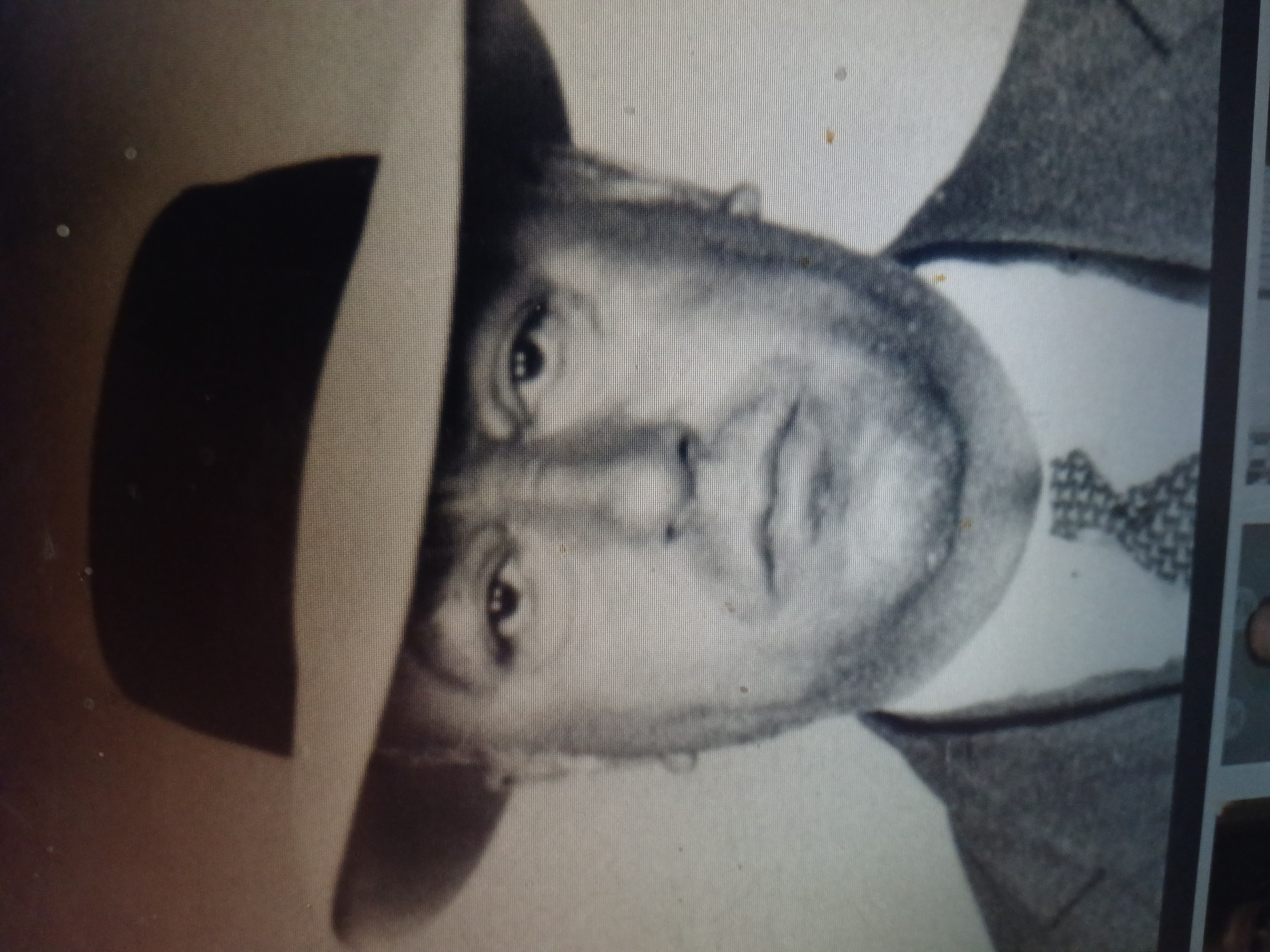

IRVING “WAXY” GORDON

“THE BEER BARON OF THE LOWER EAST SIDE”

Blog by Renee Meyers

Irving Gordon was born in January 19, 1888 on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. He was the son of Louis and Beila Wechsler, impoverished Jewish immigrants from Lvov, Poland. Louis was employed as an expressman, or trucker. He and Beila had four children with Irving being the oldest. When Irving was 10 years old, his mother died. His father later remarried but Irving did not get along with his stepmother and thus did not have a happy homelife.

Irving was soon drawn to crime and his first experience as a law breaker was when he became a pickpocket in 1905. Irving was so adept at it that he acquired the nickname “Waxey” because, as crime writer Carl Sifakis noted, “he could slide a victim’s wallet out of his pocket as though it were coated with wax.” The surname “Gordon” was just one of Irving’s many aliases, as in “Harry Gordon.” Irving also passed himself off at various times as Harry Brown, Benjamin Lustig, Benjamin Lester, Harry Middleton, Louis Wechsler, Harry Wechsler, and Harry Burns.

Irving was arrested for pickpocketing and he did time at the Elmira Reformatory in October 1905 under the name Benjamin Lustig. Two years later he was arrested again for grand larceny, this time as Benjamin Lester, but he was not indicted. In January 1908, Irving was returned to Elmira for a short while after a parole violation in 1908. In August when Irving was in Boston, he was convicted of petty larceny (as Harry Middleton) and sentenced to four months in the House of Correction. Hardly out of jail, he was sentenced in Philadelphia, again as Harry Middleton, to two years in the county penitentiary. On June 7, 1912, Wexler was convicted of disorderly conduct under the alias Benjamin Lustig but was given a suspended sentence. The same day he was again returned to Elmira for a violation of his parole. Irving was arrested once again in Philadelphia for pickpocketing and was incarcerated for 19 months. This last arrest as a pickpocket must have convinced Irving there was no future for him in this field since he returned to Manhattan and joined the labor gang of "Dopey Benny" Fein.

Irving was described as a "gruff, powerful, thickset man," with a particular talent for roughing up or beating up a person. In 1914, while a gang street fight was going on, a municipal court clerk named Frederick Strauss got caught in the line of fire and was killed by a "stray" bullet. Although Irving was one of 13 gangsters arrested for this shooting, both himself and another gang member were the only ones tried for the murder. After a long trial, both men were acquitted.

In July, 1915, Irving spent two years in Sing Sing for assaulting a man and robbing him of $465. He was released in 1916. This prison term was Irving’s last until Thomas E. Dewey, a special prosecutor of organized crime, prosecuted him for income tax evasion in the 1930s. Barely out of prison, Irving was arrested for felonious assault on March 16, 1917. Irving, who stated his name was Harry Brown was released four days later. In June 1919 Irving was arrested as Harry Gordon for disorderly conduct; again, the case was dismissed.

After Irving was released from prison, he returned to Manhattan to discover that "Dopey Benny" Fein had left the labor gang. Irving began working with several other gangs as a labor goon, strike breaker, dope peddler, and robber – until Prohibition came along. In the fall of 1920, Irving met Max "Big Maxey" Greenberg who had recently left St. Louis for Detroit. While in Detroit, Max began smuggling whiskey from Canada. Once Max realized how profitable this business was, Max decided to expand but needed $175,000 to do so. He arrived in New York hoping that Irving could help him obtain financing from a man named Arnold Rothstein, known by the moniker the "Big Bank Roll." Arnold agreed to finance the venture, if the liquor was purchased and brought in from Great Britain. Irving, who was a middleman, asked to be included in the deal and was cut in for a small "piece." From this piece, Irving launched such a successful rum-running empire that he became a wealthy man.

After Arnold ended his partnership with the two in 1921, Irving continued to help finance their business. Irving took over two large warehouses when they split up, one in the city and the other on Long Island. Arnold utilized Irving’s speedboats to smuggle in diamonds and drugs. Just as it was with rum running, it was Irving who saw the large profit potential in narcotics and later pitched it to Arnold. Irving lacked the finances to enter the racket on a large scale.

Irving formed a gang of hoods from his old neighborhood to assist him with the rum-running business which was located in the Knickerbocker Hotel on 42nd Street and Broadway. The liquor was obtained from "Rum Row," the fleet of ships anchored off the coast of New York and New Jersey. Then it was brought ashore and transported to warehouses. There, it was cut and stored, and then sold to restaurants, clubs, and bootleggers in New York.

Irving lived in a lavishly decorated, 10-room apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and owned a large home on the Jersey Shore. In his book, The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Gangster in America, Albert Fried describes Irving’s transformation from street thug to "a captain of the bootleg industry: Due to Prohibition, Irving rose during the 1920's to become beer baron Waxey Gordon.

On September 23, 1925, the United States Attorney, Buckner, conducted a raid against, as he termed it, "the biggest bootleg ring in the country, " which was run by Irving. In spite of all the publicity, a worldwide manhunt, and various indictments, nothing came of the charges. The New York Times commented on Apr. 28, 1933, that although Irving was "often punished while an unimportant thief he enjoyed immunity when he became a big racketeer. " In the summer of 1931, in order to curb intergang bloodshed, Irving was named head of the New York branch of the bootleggers. According to the New York Times of August 3, 1931, "He was the one man with the brains, the engaging and popular personality, and nice sense of justice needed for an arbiter in their colossal, illicit ventures. "

In 1925, government agents, who had been scrutinizing Gordon’s operation, got lucky when Hans Furhman, one of Gordon’s ship captains, became displeased with the amount of money he received from one of the shipments. Furhman decided to retaliate by alerting the authorities about a Canadian ship enroute to Queens with a hidden cargo of liquor consigned to Irving. On Sept. 23, agents raided Irving’s headquarters, arresting everyone there, including Maxey Greenberg, and seizing maps, charts, and radio codes. Irving, who was headed to a European family vacation was arrested upon his return. Prior to the start of Irving’s trial, Furhman mysteriously died while in a guarded New York hotel room. The police ruled it a suicide and the case against Irving was dismissed.

After Irving’s rum-running operation was exposed and his boats seized, his business folded and he moved to Hudson County, N. J. Irving joined Maxie Greenberg and Jimmy Hassell in the bootlegging business and he opened several breweries that were licensed to produce near-beer. Irving rigged the breweries to produce the "real stuff." By 1930, Irving was the main supplier of bootleg beer to northern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. He paid off Jersey City Mayor Frank Hague and his political crew for their political protection. Irving operated legal near-beer breweries in Patterson, Newark, Union City, and Elizabeth in order to throw off law enforcement. Trucks left daily from these breweries with legal near-beer shipments. Meanwhile, the genuine beer was produced in the same vats, but before it went through the de-alcohol zing process, it was pumped by underground pipes to bottling plants. Gordon hired a gang of triggermen headed by Abner “Longy” Zwillman to make sure both Irving’s near and real beer reached their destinations.

By 1931 the Wexler breweries at Paterson and Union City were returning profits at the rate of $2,277,000 per year. Gordon purchased $10 shirts, rode in limousines, kept an elaborate apartment with three master bedrooms, a library, a living room, a dining room, an American walnut bar, a stained-glass window. He spent $4,200 for leather-bound volumes by Scott, Dickens, and Thackeray.

Irving joined an alliance with future National Crime Syndicate founders Charles Luciano, Louis Buchalter, and Meyer Lansky. Irving, however, constantly fought with Lansky over bootlegging and gambling and soon a gang war started between the two men; several associates on each side were killed. Irving and the mobster, Meyer Lansky began to quarrel openly, much to the embarrassment of their various partners. The dispute reached such bitter proportions that they accused each other of being double-crossers and liars. Once they came to blows, but Charlie Lucania (Luciano) stepped between them and told them to ‘behave.’ The feud was long-lasting and by 1931 had become known in the underworld as the ‘War of the Jews.’ Soon a gang war started between the two men; several associates on each side were killed.

Finally, Charlie Lucania decided to take stronger action, because the dispute between his two friends threatened to disrupt their business. It was obvious that the organization could not contain both Meyer and Waxey.’ Lansky, with Luciano, supplied Attorney Dewey with information leading to Gordon's conviction on charges of tax evasion in 1933.

Gordon had a large million-dollar operation that included many trucks, buildings, processing plants, and associated employees and his business front could not account for this ownership and cash flow and he paid no taxes on it. Gordon was sentenced to ten years' imprisonment. At this time, he was married to a rabbi's daughter and their son was in medical school. This son died in a weather-related automobile accident while traveling from an out-of-town college planning to plead with the judge for leniency with his father's sentence. Gordon had tried to insulate his respectable family from his organized crime career and the incident was a shock to their relatives, a good deal of stress was put on the deteriorating marriage.

Irving and the mobster, Meyer Lansky began to quarrel openly, much to the embarrassment of their various partners. The dispute reached such bitter proportions that they accused each other of being double-crossers and liars. Once they came to blows, but Charlie Lucania (Luciano) stepped between them and told them to ‘behave.’ The feud was long-lasting and by 1931 had become known in the underworld as the ‘War of the Jews.’ Finally, Charlie Lucania decided to take stronger action, because the dispute between his two friends threatened to disrupt their business. It was obvious that the organization could not contain both Meyer and Waxey.’

By mid-1931 cooperation between Irving and Lansky had become impossible. Besides his feud with Lansky, Irving was facing an investigation of his income tax returns by the Internal Revenue Service. According to Luciano, he and Lansky formulated a plan to provide incriminating evidence to the IRS to help them put Irving away. The plan was allegedly carried out by Lansky’s brother, Jake, who was said to have several friends who were IRS agents. Jake traveled to Philadelphia and supplied the agents with financial information that led to the indictment of Irving. Thomas E. Dewey was the prosecutor for the Gordon tax trial. If there was any truth to Luciano’s statement, Dewey never acknowledged it.

With the conviction achieved in Chicago against Al Capone, the special agents of the Intelligence Unit of the IRS were reassigned to New York to begin the same process on East Coast bootleggers Waxey Gordon and Dutch Schultz. For two years, six investigators worked full time to obtain evidence on Irving that would stand up in court. During the final six months, a half dozen lawyers and twelve IRS agents formed the task force against Irving.

While Irving prepared himself for the onslaught of government agents, he was also engaged in another battle. The newspapers claimed that the threesome including Irving, Greenberg, and Hassell had killed those who got in the way of establishing their lucrative bootleg business. Local bootleggers James "Bugs" Donovan and Frank Dunn were involved in this killing. With Irving now facing legal problems, his enemies struck back. The New York Times stated that it was a North Jersey gang, made up of the "remnants of the one deposed" by Irving’s gang, that made its move.

In April 1933, Irving testified that while he, Greenberg and Hassell were meeting at the Elizabeth Carteret Hotel in Elizabeth, N. J., he heard "sort of like a rattle of dishes out in the hall." When he went to check, he observed "some of the men that worked for Mr. Hassell and Mr. Greenberg running along the hall." He claims the men told him “They just shot Max and Jimmy." Irving, however, said he was unable to identify any of the men in the hallway that day. In Mark Stuart’s biography of Abner "Longy" Zwillman, Gangster #2, Stuart stated that gunmen sent by Dutch Schultz were the shooters and that Irving escaped by jumping out a window.

After the shooting, Irving hid out at his Sullivan County hunting lodge. Gordon kept two bodyguards available, a speedboat docked by the lakeside, as well as a pistol under his pillow. He stayed there until May 1933 when government agents finally located him down and brought him back to be charged with income tax evasion.

In his book, Thomas E. Dewey enumerated several tasks the agents had to perform to prepare the indictment against Irving: Agents needed to find out, "For example, who sold the beer barrels to the Gordon breweries? Who sold the malt? Who sold the fleet of trucks the Gordon organization used for distribution? Who sold the oil, the gasoline, the tires, the brewing machinery, the cooperage coating, the air compressors, the cleaning compounds, the kettles and pipes, the hops, the yeast, the repair parts for the trucks, and the materials for repairing beer barrels, the heads, shook’s, and rivets? Who installed the piping and the electrical equipment?" "How were all these goods and services paid for, and in whose names had delivery been taken? What did the sellers’ books show about the checks and who had signed them? On what banks had the checks been drawn?"

Dewey claims in several instances the agents were in a foot race to obtain the company records and banks before Irving’s men did. They frequently lost. The agents investigated companies and found that accounting entries had been re-written where they involved Irving. There were times when agents went into New Jersey banks and were told to sit and wait. Soon Irving’s men would show up and withdraw all of the money from his account and remove any evidence of the account’s ownership. One-time agents were arrested by the local police in a Hoboken bank. They were held until Irving’s men arrived and carried off the records.

Samuel Guroch, was one of Irving’s employees who who had opened a number of bank accounts under fictitious names. Guroch had been issued a subpoena to appear for questioning and ignored it. In June 1932, agents located him and he was held in jail for contempt. His hearing was set for the following morning. In the middle of the night, Frank J. Pfaff, a U.S. Commissioner, arrived at the jail and set the bail for Guroch at $500. Guroch promptly posted bail, walked out, and was never seen by the investigators again.

Although Irving never opened a bank account in his own name, he was careless at times and took many risks. He endorsed checks with his name or the name on the dummy account that had been set up. Dewey stated that the handwriting expert who was assigned to the case "did more than any other single factor to tie the whole case together."

As Dewey’s investigation continued, Irving continued to defend himself. The district attorney of New York, Thomas C.T. Crain announced that he would initiate an investigation of Gordon. However, after a few weeks, Crain gave up, noting that there were no witnesses brave enough to testify against Irving. Dewey stated that this incident caused one of the darkest days in this investigation since many of the witnesses the prosecution had lined up suddenly forgot everything they had to say.

Dewey’s men continued their work. By the conclusion of the two-year investigation, the men had interviewed over 1,000 witnesses, reviewed 200 bank accounts, traced the toll slips of more than 100,000 phone calls, and sat through several thousand hours of grand jury examination. Irving was indicted for attempting to evade payment of federal income taxes. The indictment at trial time claimed he had an unreported net income of $1,338,000 for 1930, and $1,026,000 for 1931. The agents came to arrest him at his hideout, a summer cottage at White Lake in the Catskill Mountains.

When the trial opened on Nov. 20, 1933, Dewey introduced the Gordon empire to the jury. He presented information on the two breweries, washhouses for the barrels, drops for the delivery and concealment of the beer, the barrels, a vehicle repair garage, five offices, two houses, several hotel suites, and 60 Mack trucks. After nine days, 131 witnesses, and over 900 exhibits, Dewey rested his case. It was now up to Irving to prove how he acquired these assets with a net income of $8,100 that he claimed for 1930.

Irving’s attorney tried to convince the jury that the business had been owned and operated by the now deceased Greenberg and Hassell. Any wealth Irving had accumulated had been given to him by the two men. When the defense called upon an insurance man to prove that Irving was actually a poor man, Dewey demolished his credibility by producing several memos sent to the insurance company that showed Gordon’s heavy investments in several hotels.

The final defense witness was Irving himself. His testimony proved pathetic: He claimed to be "lured" into the beer business, and "lured" into investing in the hotels by Greenberg and Hassell. When presented with the paperwork for a building loan where he had signed one personal guarantee for $1 million and another for $795,000, his answer was simply that it was "just a favor" for Max Greenberg. Irving testified that none of the brewery employees worked for him, instead they worked for "Max and Jimmy."

Irving tried to convince the jury that what he did he did for his family, but he struggled noticeably under the young prosecutor’s cross-examination. At one point, Dewey’s assistants recommended that he conclude his examination because Irving, "looking physically sick," would gain sympathy from the jurors while under such pressure.

The case was sent to the jury on Dec. 1, 1933 at 3:34 p.m. A verdict was reached in just 5l minutes. The jury foreman announced, "We find the defendant guilty on the first count, the second count, the third count and the fourth count." The newspapers reported "Gordon’s jaw sagged and his dark eyes (were) fixed in hatred on the men in the jury box as their verdict was pronounced." Seated behind Gordon was his wife Leah, who cried openly as the verdict was read.

The judge fined Irving a total of $80,000 and sentenced him to 10 years in the federal penitentiary in Atlanta. In addition to his conviction and jail sentence, Irving suffered a personal tragedy as well. Over the years Irving had tried to shield his family from his criminal activities. His wife, Leah, the daughter of a rabbi, endured a good deal of shame. Irving’s oldest son, Theodore, was in his first year of pre-med. at the University of North Carolina. Irving was proud of his son and often bragged about him. Throughout the trial, Theodore remained in New York with his mother, but returned to school after the verdict was announced. Nathan Wexler, Irving’s brother, called Theodore and urged him to return to New York a few days later to plead to the judge and Dewey for a reduction in sentence for his father, and for Irving to be freed on bail while an appeal was pending. When he was on his way back to New York, Theodore was killed in a car accident on snow and sleet covered roads.

In 1940, Irving was released from Leavenworth Penitentiary after serving seven years. Upon leaving he declared, "Waxey Gordon is dead. From now on its Irving Wexler salesman." Irving, now divorced, traveled to San Francisco in the summer of 1941. At this point, it was reported that Irving still owed the government $2.5 million in back taxes. The San Francisco police officers found Irving registered at an expensive hotel. Irving explained that he had come West to make a new start and was selling a "revolutionary type of cleaning fluid." Although he had over $400 in cash on him, the police arrested him for vagrancy. He posted $10 bail and left town.

During World War 11, when America began sugar rationing, Irving was caught selling 10,000 pounds of the sugar to an illegal distillery. He was convicted and served a year in jail.

Irving became involved in the drug trade and by 1950 the Narcotics Bureau had a substantial file on him. In December 1950, the bureau used ex-convict Morris Lipsius to befriend Irving and set him up for what would be his final arrest. After two successful drug transactions, Irving was caught on Aug. 2, 1951 by federal agents for selling heroin. The 62-year-old gangster reportedly offered the detective all his money in exchange for his freedom. When the detective refused the offer, Gordon jokingly pleaded with the detective to kill him instead of arresting him for "peddling junk." Irving was not simply facing a sentence for heading a narcotics ring that was believed to have international connections, but as a four-time offender to the "Baumes Law."

Irving pled not guilty to two counts of narcotics trafficking. He was one of 23 people indicted in this nationwide narcotics case. The trial, with the remaining 10 people, was set to begin on Aug. 18. Irving was originally being held in the San Francisco County Jail, but was transferred to the federal facility on Alcatraz. New York of General Sessions Judge Francis L. Valente found Irving guilty and due to his long criminal record was sentenced to 25 years to life. During the sentencing, Valente told the court: "Since his (Irving’s) first act of lawlessness forty-six years ago, his contempt for authority manifested by progressively more serious criminality, has been like a malignant cancer, weakening the dignity and good order of the community." Turning to Irving the judge chastised him saying: “You have demonstrated repeatedly that there is no crime or racket to which you would not resort in order to make a dollar. Your latest and most dastardly offense is typical of your hostility, and it should ring down the curtain on your parasitical and lawless life."

Irving had been ill for some time and was confined to the Alcatraz prison hospital. He was sitting in a chair speaking to a physician when he suffered a massive heart attack and died. Irving Gordon was 64 when he died in 1952 and he was buried at Mount Hebron Cemetery in New York.

~Blog by Renee Meyers