Story Summary:

We implore you to discover more about the tragic and mysterious passing of David Traub, an Army veteran who as killed at the age of 21. May his memory and life be a blessing to all. ~Blog Written by Michael Ackermann

We implore you to discover more about the tragic and mysterious passing of David Traub, an Army veteran who as killed at the age of 21. May his memory and life be a blessing to all. ~Blog Written by Michael Ackermann

Casualty of Animosity

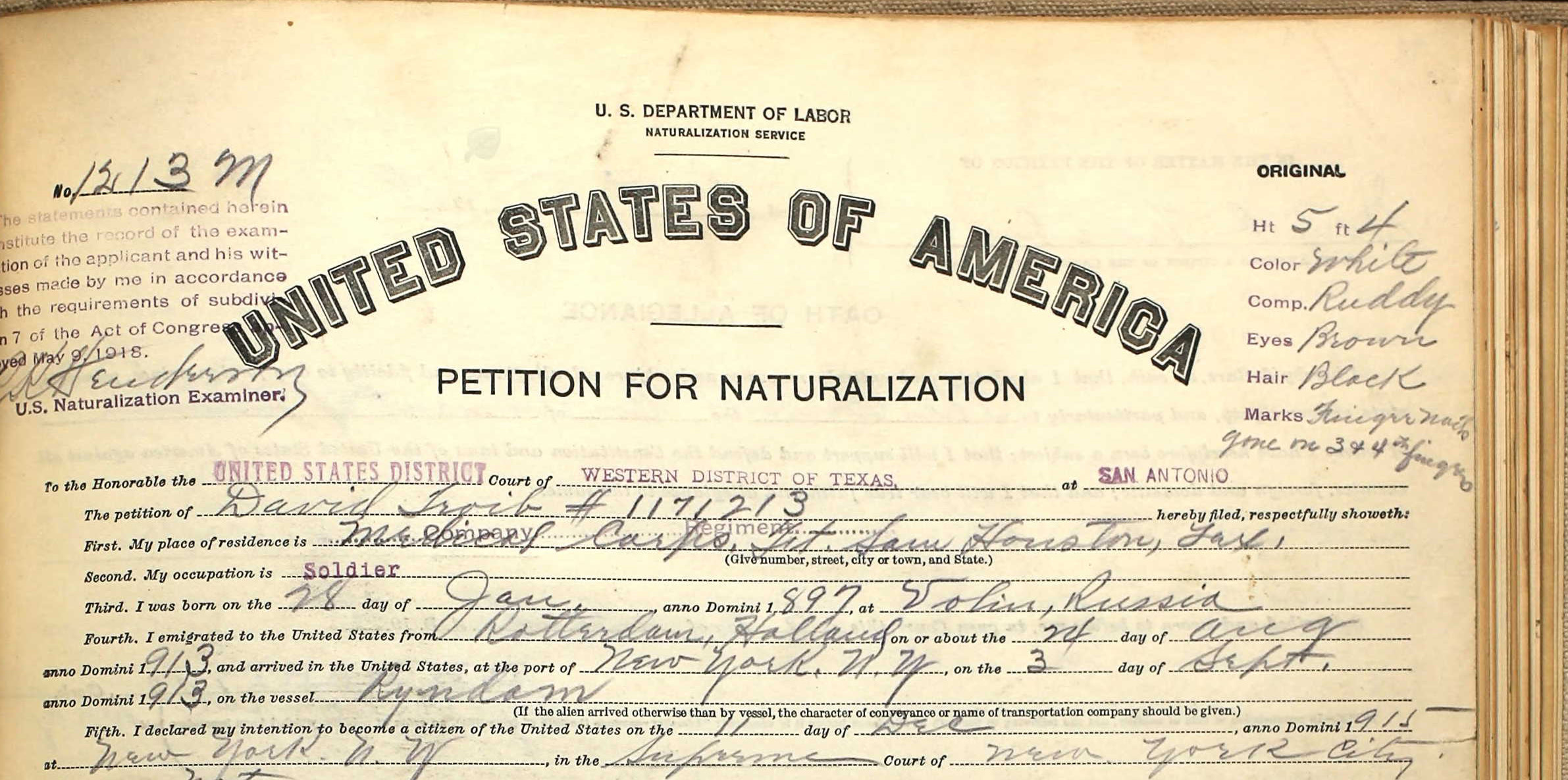

I am not a disbeliever in or opposed to organized government or a member of or affiliated with any organization or body of persons teaching disbelief in or opposed to organized government. I am not a polygamist nor a believer in the practice of polygamy. I am attached to the principles of the Constitution of the United States, and it is my intention to become a citizen of the United States and to renounce absolutely and forever all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty, and particularly to the Present Government of Russia of whom at this time I am a subject, and it is my intention to reside permanently in the United States.[i]

David Troib, a 21-year-old Russian immigrant, signed his name to these words on a United States Petition for Naturalization on September 5th, 1918. By the end of the year, he would be dead in El Paso, Mexico.

David began life in Eastern Europe in what was Volyn, Russia, now a region of Ukraine. Born January 28th, 1897, he made his way to the United States in the late summer of 1913 at 16 years old, arriving in New York. In June 1916, David enlisted in the U.S. Army at Fort Slocum in the hopes of solidifying his citizenship. World War I was already in full swing over in Europe, the United States had not joined the fray yet. Though David did not leave any written records, it would be fair to assume that as a 19-year-old who had spent the past three years building a life for himself in the United States, the idea of returning to Europe was unappealing but it was a risk he was willing to take in order to prove himself and earn his place. This was a path followed by many immigrants in the early 20th century through to the post-WWII era.

Most likely unbeknownst to David, two and a half thousand miles away, Mexico was in the middle of a revolution. The original goal of the Revolution was to depose the government of Porfirio Díaz, the dictator of Mexico from 1876 to 1911. Díaz’s rule was largely based on corruption and military might. It was not until 1911 that Francisco Madero was able to unite various revolutionary branches into one force able to depose Díaz. Madero brought his forces together in Chihuahua, Mexico in February and by October was elected President of Mexico. Madero’s rule did not last long though. His politics did not sit well with either the right or the left. He was forced to deal with multiple revolts from both supporters of the old regime and revolutionaries who sought greater reforms than Madero was willing to provide. The same year David stepped foot in the United States in 1913, Mexico saw what was later referred to as “Decena Trágica”, Ten Tragic Days, in which Mexico City became a battleground of revolution.[ii] With this attack, Madero was removed from office and later killed by his escort while transferring prisons.

The climate in Mexico was further intensified by foreign intervention. Centuries of foreigners invading, and seizing control had left the Mexican people with a healthy distrust of Westerners’ intentions. The 18th century saw the greatest bolster to this distrust. Under Spanish control, Mexico was constantly forced to pay the costs of Spanish affairs, something the former colonists north of the border should have been more understanding of.[iii] In 1914, President Woodrow Wilson decided to send troops into Mexico in order to remove Victoriano Huerta, one of the potential Presidents of Mexico. This actually worked to unify most of the revolutionary leaders. Venustiano Carranza eventually came out of this turmoil as the acting President. In 1917 he reformed the constitution aiming to find a way to appease all the revolutionary factions.

Along the border between the United States and Mexico, tensions rose. In 1912, a Mormon settlement that had been established in Mexico for decades was forced to return to the U.S..[iv] The colonies had been established in 1885. The Mormons were faced with much difficulty at first since their ideals clashed with local politics. Under Díaz, the Mormons were able to find a safe haven under the agreement that Mexican citizens be included in these colonies. This went well for a bit, but the clash of cultures became too much and most of the Mexican inhabitants of these colonies returned to their own villages.[v] In 1912, amidst the turmoil of revolution, Orozco’s rebels forced the Mormons to surrender their weapons while simultaneously removing their guarantee of protection. This prompted the colonists to send the women and children to El Paso in hopes of keeping them safe. Shortly afterwards, the remaining colonists would join them.

In the United States, Mexicans received equal prejudice. “In 1910, a white mob in Rocksprings, Texas, lynched 20-year-old Antonio Rodríguez and burned the body after he was accused of killing a white woman. He never received a trial; instead, he was kidnapped from jail.”[vi] This is just one of a plethora of examples of violence wrought upon Mexicans in the U.S. and shows the degree of distrust and disdain the two sides had amassed.

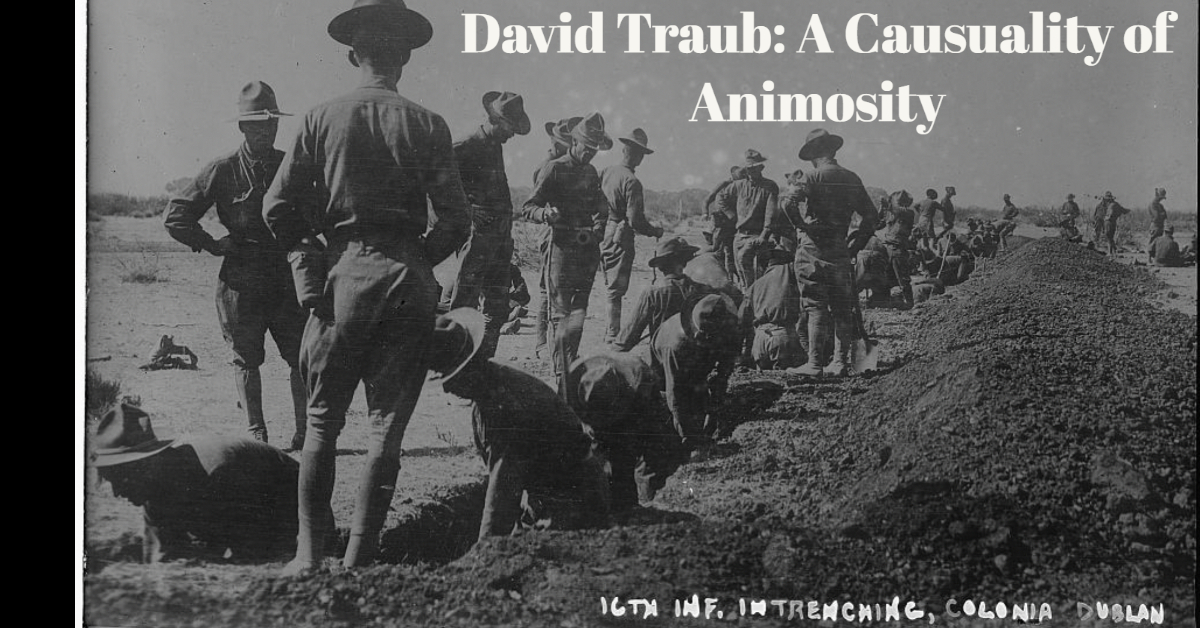

In 1916, the United States negotiated with Carranza to send a military expedition into the country to hunt down Pancho Villa for his raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Carranza at first refused, stating that his forces would hunt down Villa. Eventually Carranza conceded and allowed the troops in. The U.S. troops eventually found themselves entrenched at Colonia Dublan, one of the former Mormon colonies. The soldiers were constantly struggling to make progress due to slow and unreliable supply lines and issues with communication “since the Mexicans made a sport of cutting the wires”.[vii]

Meanwhile, in June of 1917, David entered active duty. In February 1918 he was deployed to Fort Sam, Houston, Texas, as part of the Hospital Base. By this time David must have known about the amount of tension that was prevalent in the region. Even if David did not know what he was walking into, he must have learned quite quickly what the situation was. “Fort Sam Houston itself served as a mobilization point and staging area for virtually the entire National Guard, called up by President Wilson to protect the border.”[viii] Everyday David would have been in direct contact with soldiers who patrolled the boarder. It is interesting to wonder what David’s opinions on the whole affair were. Afterall, he had joined the army to aid in gaining his citizenship to the United States, now he was literally being charged with protecting the very nation he sought to join.

Tensions between Mexico and the United States erupted along the border on August 27th, 1918. Nogales, Sonora, and Nogales, Arizona are twin cities on the border of the United States and Mexico. The location provided an excellent trade route between the two nations and provided economic benefit to citizens on both sides. Cooperation was key to making the cities work. It is unclear who fired the first shot on that day but quickly the twin towns were at war. Soldiers took positions in the upper stories of buildings, International street became no man’s land, and people fell on both sides.[ix] By the time the chaos had subsided over approximately one hundred and fifty people were killed or wounded, mostly on the Mexican side. Claims were made that the Americans attacked first, and the Mexican side consisted of civilians, not soldiers. Capitan Frederick T. Herman of the U.S. stated that “most of the Mexicans engaged were soldiers, although a majority wore civilian clothes, and that the fighting had been planned and was directed by their commanding officer and his assistants.”[x]

To add to the already existing tensions, the concern of German interference was also prominent. Due to the Zimmermann telegraph, an intercepted message from Germany in 1917 that sought an alliance with Mexico, promising the return of land lost during the Mexican War years before, Americans were preparing for a full-scale war.[xi] Following the battle, claims were made that Germans soldiers were found fighting on the Mexican side.[xii] In the minds of the American soldiers, The Great War was being fought at the very gates of their homeland.

Tensions were high for months following the battle. The United States and Mexico were constantly passing the blame for the escalation and because of this both sides were ready to kill. On December 27th, 1918, David Troib was shot and killed just pass the Mexican border by Mexican Lieutenant Juan Azpieta. The United States demanded answers for this murder. Azpieta claimed that the shooting was in self-defense but witnesses from both sides testified that David was unarmed. The case was to go before a court-martial in Chihuahua, Mexico.[xiii] David’s body could not even rest in peace. Mexican authorities insisted that he needed to be exhumed three times from Mount Hebron Cemetery in Queens, N.Y..[xiv] The investigation determined that he was shot from the side at a close range.

During the preliminary trial, Azpieta confessed to the shooting but maintained it was in self-defense despite the witness testimonies. In the weeks before the official trial was set to begin, Azpieta was moved to Chihuahua City as to be closer to the court. On November 30th it was revealed that Azpieta had vanished which led to accusations “that the Mexican officer never was properly confined after leaving Juarez and that his removal was a ruse to prevent a serious trial.”[xv] The United States kept returning to this case in their dealings with Mexico, reexamining the evidence and testimonies and pushing for Azpieta to be found and brought to justice. Unfortunately, no evidence can be found today on whether authorities ever found Azpieta or if he ever faced his court-martial. In an era that was wrought with distrust and animosity between multiple nations, David Troib, a young man simply seeking a home, became a victim of forces beyond his control.

~Written by Michael Ackermann

[i] The National Archives at Fort Worth; Fort Worth, Texas; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: 21

[ii] “The Mexican Revolution and Its Aftermath, 1910–40,” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/place/Mexico/The-Mexican-Revolution-and-its-aftermath-1910-40.

[iii] Hubert Howe Bancroft, “Causes of Disaffection in Mexico,” Essay, In History of Mexico: Being a History of the Mexican People from the Earliest Primitive Civilization to the Present Time, 268–77, (New York, NY: The Bancroft Co., 1914).

[iv] Philip R. Stover, “The Exodus of 1912: A Huddle of Pros and Cons—Mormons Twice Dispossessed,” Journal of Mormon History 44, no. 3 (2018), 45–69. https://doi.org/10.5406/jmormhist.44.3.0045.

[v] Elisa Eastwood Pulido, “Mormonism in Mexico - the Mormonism and Migration Project The Mormonism and Migration Project,” The Mormonism and Migration Project, January 23, 2022. https://research.cgu.edu/mormonism-migration-project/study-resources/mormonism-in-mexico/.

[vi] Russell Contreras, “Mexican Americans Faced Racial Terror from 1910-1920,” AP NEWS, Associated Press, (July 26, 2019), https://apnews.com/article/texas-us-news-ap-top-news-az-state-wire-ca-state-wire-b8516a3d80ef40da97afd3a9e4f7d706.

[vii] Mitchell Yockelson, “The United States Armed Forces and the Mexican Punitive Expedition: Part 2,” National Archives and Records Administration, National Archives and Records Administration, (Accessed May 11, 2022). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1997/winter/mexican-punitive-expedition-2.html.

[viii] “The Fort Sam Houston Museum,” The Fort Sam Houston Museum - U.S. Army Center of Military History, (Accessed May 11, 2022), https://history.army.mil/museums/fieldMuseums/FSHMuseum/index.html.

[ix] “Battle of Ambos Nogales Led to the First Fence Separating ... - Youtube.” (Accessed May 14, 2022), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QaiUZzp_lck.

[x] “Two Germans with Carranza in 1918.” The Kingsport Times. February 13, 1920.

[xi] Telegram from United States Ambassador Walter Page to President Woodrow Wilson Conveying a Translation of the Zimmermann Telegram; 2/24/1917; 862.20212 / 57 through 862.20212 / 311; Central Decimal Files, 1910 - 1963; General Records of the Department of State, Record Group 59; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/translation-zimmermann-telegram, May 13, 2022]

[xii] “Two Germans,” The Kingsport Times, February 13, 1920.

[xiii] “Courtmartial Mexican Who Shot US Soldier,” Nevada State Journal, (February 3, 1919).

[xiv] “Exhume Body for Evidence,” Times Union, (September 13, 1919).

[xv] “Slayer of U.S. Soldier Missing on Trial Date,” San Antonio Express, November 30, 1919, Vol. 54, No. 331, Ed. 1 edition.