Story Summary:

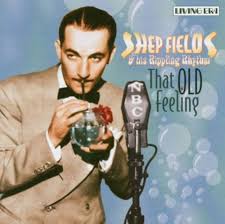

Shep Fields was a popular jazz band leader of the 1930s and '40s, best known for his "Rippling Rhythm" trademark, which featured Fields blowing bubbles into a bowl of water at the beginning of every song and wood-block playing by the band's drummer. Among the highlights of Shep Fields career was his band being featured in the film "The Big Broadcast of 1938," which starred W.C. Fields and Bob Hope, and conducting his band. He had his own NBC coast-to-coast radio broadcast and conducted his orchestra at the Academy Awards ceremony in Los Angeles in 1939.

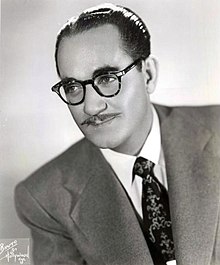

Shepp Fields: Jazz Band Leader

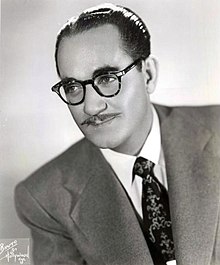

Shep Fields was born in Brooklyn, New York on September 12, 1910 and was named Sheppard (Saul) Feldman at birth. Shep’s parents were Mr. Fields and Mrs. Sowalski Fields. His father, who owned The Queen Mountain Guest House in the Catskill Mountains, passed away at 39 years of age. Shep had two brothers named Edward and Freddie. Freddie, Shep’s younger brother, was a respected theatrical agent and film producer while Edward was a carpet manufacturer. Shep was married twice and his wives were Zook Kline and Evelyn Feinstein. Shep was the brother-in-law of actress Polly Bergen.

Shep began his musical career by playing clarinet and tenor saxophone in bands during college. His band was called "Shep Fields Jazz Orchestra." Shep’s band made frequent appearances at his father's resort hotel which also hosted such noted singers as Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor.

Shep began working on a degree at a law school. Following the death of his father, Shep was forced to become his family's principal provider. Consequently, he dropped out of law school and reformed his orchestra.

Shep had an idea to concoct a unique orchestral sound to distinguish his ensemble from other bands of his era. With this in mind, he collaborated with his arrangers to analyze the performances of his peers. After admiring the sounds featured by the trombone in Wayne King's orchestra, Shep adapted them to his viola section. The embellishments for the right hand, which were popularized by Eddy Duchin on the piano, inspired the elegant passages that Shep assigned to his accordionist. Shep was also impressed by Hal Kemp's use of triplets on the trumpet and Ted Rito's use of temple blocks. As a result of the variety of these orchestral sounds, Shep incorporated the unique sounds of the clarinets, flutes, and temple blocks in his orchestra. After he listened to Ferde Grofe's innovative use of the trombone and temple blocks, Shep adopted a similar for his muted trumpets.

The resulting sound of Shep’s band impressed the radio listeners on the Mutual Radio Network. There was a contest held in Chicago for fans to suggest a name for Shep’s band now that it had a new sound. Several fans chose the name "rippling" and Fields used to word to the band’s new name: "Rippling Rhythm.” Shep and his band began making appearances on cruise ships and at resort hotels.

Shep’s first big break came when he was invited to become conductor for the Veloz and Yolanda dance team in 1932. Soon, Shep’s orchestra was booked at the famed Roseland Ballroom in New York City. By 1933, Shep’s band played at Grossinger's Catskill Resort Hotel. In 1934, Shep replaced the Jack Denny Orchestra at the landmark Hotel Pierre in New York City. Shep soon left the Hotel Pierre to join a roadshow with the dancers. They toured though the US eastern seaboard also in Canada and Argentina, after which time Shep was offered his own NBC coast-to-coast radio broadcast in 1935 which he called Rippling Rhythm Review. In 1936, he signed with Bluebird Records. 1936, Shep was booked at Chicago's Palmer House Hotel, and the concert was broadcast live on the radio.

Shep Fields soon attracted national attention. He was soon invited to play at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles. Shep returned to his former position at the Hotel Pierre in New York City. As Shep was returning to New York, he heard a distinctive sound that he decided to use to introduce his "Rippling Rhythm" show. By 1937, Shep was also featured on the NBC radio network in his own show called, Rippling Rhythm Revue. His highly successful "Rippling Rhythm" band was subsequently featured regularly on a hotels big band remote concert, which were transmitted over the radio to audiences throughout the country.

One day Shep and his wife Evelyn were relaxing at a Rockford, Illinois soda shop. He had thus far been unsuccessful in his attempts to develop a studio sound effect to introduce his music in Los Angeles. As Evelyn and Shep were brainstorming, Evelyn began blowing bubbles into her soda through a straw. That was the inspiration that Shep needed. He immediately decided to use that sound and it became the trademark which opened each of Shep’s shows. Shep’s new shows featured himself blowing bubbles into a bowl of water at the beginning of every song and a good deal of wood-block playing by the band's drummer. Though he was constantly kidded about the sound, it served as a memorable trademark throughout the band’s existence. In that regard, Fields' style was actually a predecessor to Lawrence Welk's "Champagne Music" style. In 1937 Shep recorded this unique theme song for Eli Oberstein on RCA Victor's Bluebird label.

It was his light and elegant musical style which made Shep consistently popular among audiences throughout the 1930s and into the 1950s. As a result of this widespread popularity, Shep received a contract with Bluebird Records in 1936. His hits included "Cathedral in the Pines", "Did I Remember?", and "Thanks for the Memory". Shep performed at Broadway's Paramount Theater and consistently broke attendance records.

He performed at the posh "Star-light Roof" atop the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in 1937. Shep replaced the musician Paul Whiteman with his own radio show, The Rippling Rhythm Revue. This revue featured a young actor named Bob Hope as the announcer on the NBC network. In 1938, Shep had his first motion picture which featured The Rippling Rhythm Orchestra and Hope. A series of live remote broadcasts of the orchestra was also transmitted from the Los Angeles Biltmore Hotel featuring the accordionist John Serry Sr. By the next year, Fields remained popular with audiences nationwide. In 1939, Shep and his orchestra were invited to the Academy Awards ceremony in the historic Biltmore Hotel in Los Angeles, California. Shep began a series of USO tours designed to entertain the troops during World War II.

The orchestra produced a string of successful hits throughout the late 1930s and early 1940s, reaching the peak of its popularity in 1939, when Fields was featured on Billboard magazine’s July 15 issue.

By 1941, Fields revamped his band and he named it Shep Fields and His New Music. It was turned into an all-reeds group with no brass section. Shep’s new orchestra blended over 35 instruments, including: one bass saxophone, one baritone saxophone, six tenor saxophones, four alto saxophones, three bass clarinets, 10 standard clarinets, and nine flutes including an alto flute and a piccolo. The resulting band produced a rich ensemble sound under the guidance of prominent arrangers. Leonard Feather who was a critic, applauded the new band's beautiful sound.

While the new orchestra was initially highly acclaimed, it failed to be as popular with the public as had Shep’s earlier group. In 1947 Shep returned to his previous sound. He continued rippling into the 1950s. However, Shep’s popularity eventually waned. In 1955, Shep disbanded his group for good and became a DJ for a Houston radio station.

During the course of his artistic career, which extended from 1931 through 1963, Shep Fields compiled an extensive musical legacy that has been preserved on Bluebird Records, Mercury Records, MGM, and RCA Victor. His discography includes over three hundred arrangements of popular songs from this era and includes such hits as: "It's De-Lovely,” "I've Got You Under My Skin", "The Jersey Bounce" “Moonlight and Shadows" "That Old Feeling" and "Thanks for the Memory." Shep also engaged in acting and producing and was known for the two films: Bringing Up Father Citizens Band (1977) and a Bob Hope film called, The Big Broadcast of 1938 with W.C. Fields in the Bob Hope. In 1977 Shep made recordings for Reader's Digest. He also became a disc jockey in Houston, Texas.

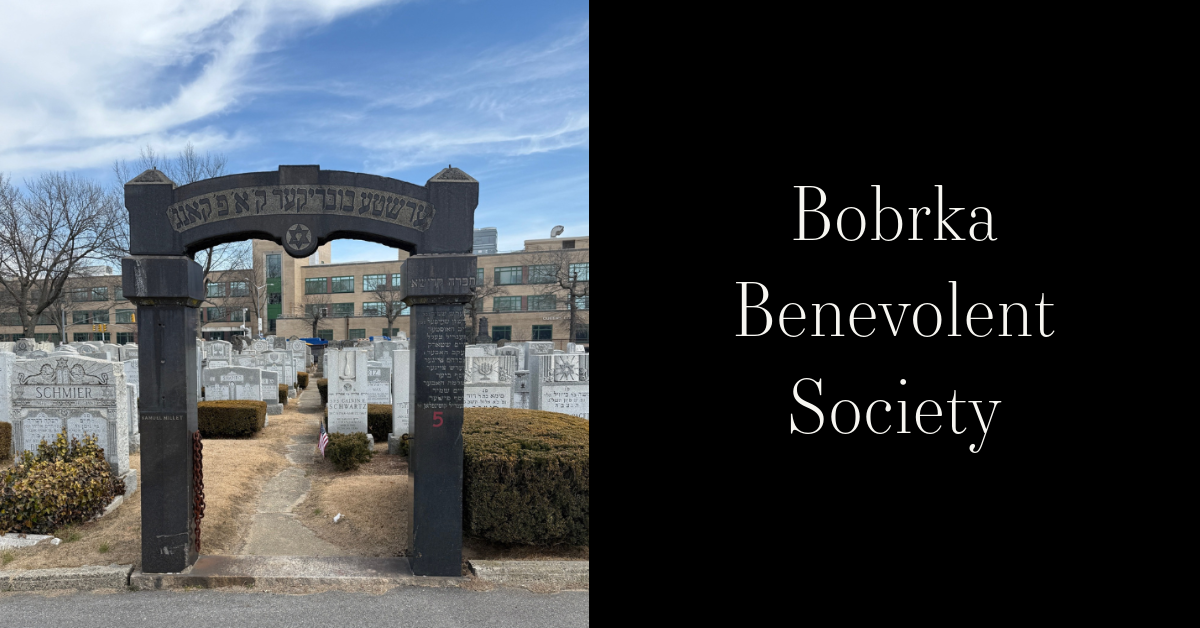

In 1963, several years after the disbanding of his group, Shep and his brother, Freddy, formed the talent agency Creative Management Associates. Shep continued working in this agency until his retirement. In February 23, 1981, Shep Fields died of a heart attack in Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles at age 70. He was buried in Mount Hebron Cemetery in New York.

~Blog by Renee Meyers