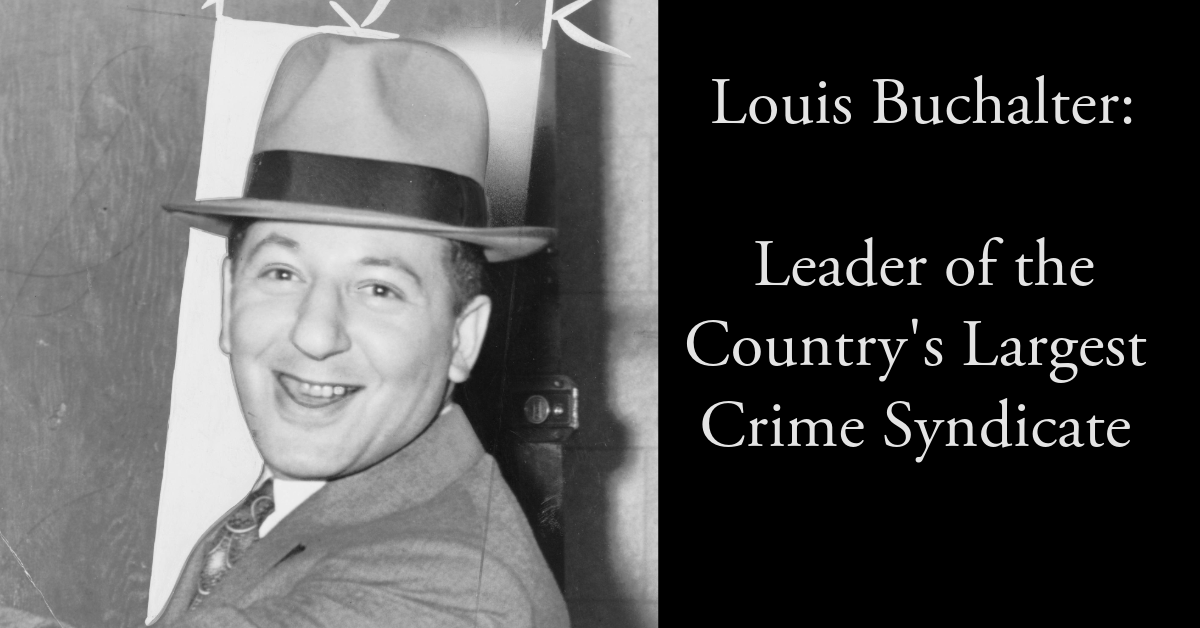

Louis "Lepke" Buchalter: Leader of the Country's Largest Crime Syndicate

Louis Buchalter was the son of Rose and Barnett Buchalter, poor East Side Jewish immigrants from Russia. Louis was born in New York City on February 6, 1897. His mother, Rose called him "Lepkeleh" ("little Louis" in Yiddish), which later became "Lepke". Both his parents had children from other marriages and by the time Louis and two other siblings were born, they were a family of 13. Louis had one sister and three brothers. For a while, they all lived in a tenement on Essex Street near Delancey Street but moved around a lot. Barnett ran a small hardware store in a shop on Henry Street but he was barely making a living. The children, including Louis, went to public and Hebrew schools. Louis’s elder half-brother became a rabbi/college professor, another a dentist and his third brother became a pharmacist. Louis’s sisters married and had families.

Barnett died in November 1909, following a diabetic coma. Louis was just 12 years old. In 1910, Louis finished elementary school and started a job selling theatrical goods. Louis also attended the Rabbi Jacob Joseph School on the Lower East Side where he was an "honor roll" student.

Barnett’s death was hard on Rose, who, while struggling to make a living, tried to make money selling food to her neighbors. In 1912, Rose moved out of New York leaving Louis and her other younger children with their older half-sister Sarah. Rose relocated to Arizona or Denver, where she spent part of the year in a city where one of her sons lived. With his mother gone, Louis began to regularly get into trouble and his behavior was eventually beyond Sarah’s control.

It is possible that Louis’s mother’s absences were the reason Louis got into trouble as a young teenager. Louis’s behavioral issues may also have been the result of his interaction with the other East Side Street kids. Either way, once Louis’ life of crime started, it did not conclude for the next three-and-a-half decades.

Louis began his criminal career by robbing pushcarts and stealing produce when still a teenager. He met a boy named Jacob “Gurrah” Shapiro when they were both trying to rob the same pushcart. The two boys soon became a formidable team.

At the height of Louis’s success as a thief, he and Jacob were raking in more than a $1 million (about $22 million or more today) annually, and they dominated (or possibly even controlled), the garment, leather, fur, baking, and trucking industries in New York and parts of New Jersey. With Shapiro’s brute strength, the two men established an extortion business, forcing pushcart owners to pay for protection.

Louis and Shapiro then added a third accomplice, a young man named Jacob “Little Augie” Orgen. Jacob’s Lower East Side gang including Louis and Shapiro turned their attention to bigger game. This resulted in Louis’s very first arrest. On September 2, 1915, when Buchalter was 18 years old, he was arrested in New York for the first time for burglary and assault. This case was eventually dismissed.

Next, Louis moved on to more substantial thievery by burglarizing tenements. In 1916, using the alias Louis Kauvar (one of dozens of aliases he used over the years; Kauvar was the surname of his mother’s first husband), Louis was arrested in nearby Bridgeport, Connecticut—where he had been residing with an uncle—for stealing a salesman’s suitcase. For this crime, Louis was sent for a year to the Cheshire Reformatory for juvenile offenders in Cheshire, Connecticut where he remained until July 12, 1917. When Louis was released, he had a disagreement with his uncle and subsequently moved back to New York City.

On September 28, 1917, when Louis was 20 years old, he was sentenced to 18 months at the state prison at Sing Sing in Ossining, New York, on a grand larceny conviction. Louis was later transferred to Auburn Prison in Auburn, New York and then Great Meadow Prison in Comstock, New York. He was released on January 27, 1919. On January 22, 1920, Louis was again arrested for attempted burglary of a women’s clothing store. He was given a 30-month sentence and was returned to Sing Sing. Louis was released on March 16, 1922 and he resumed working with his childhood friend, mobster Jacob. They spent time in Brownsville, Brooklyn where they harassed pushcart peddlers.

Louis and Shapiro, discussed embarking on a money-making scheme similar to what their acquaintance, Dopey Benny Fein, and others had done: acting as thugs for garment unions and manufacturers. The team of Louis and Shapiro became very successful and were soon known as “Lepke and Gurrah” or “L and G.”

There has been much written about these men’s clever criminal schemes, however, they were essentially extortionists. Louis and Shapiro controlled unions, placed their men in key positions, and dictated trucking and distribution for a variety of industries which often drove competing firms out of business. Louis and Shapiro demanded regular huge payments which they referred to as dues.

In 1932, this duo tried to take over the fur-dressing business and they subsequently started two corporations which were called: the Protective Fur Dressers Corporation and the Fur Dressers Factor Corporation. The mission of these corporations was to eliminate all companies and dealers who would not become members.

L & G posed only one threat to these businessmen and workers when they blackmailed the associations’ members for hundreds of thousands of dollars or charged them for protection (provided by members of their own gang) or charged them to stop a strike, which they would make happen. As the FBI later reported, the dealers and manufacturers in the fur dressing as well as other industries who defied these criminals were threatened with violence such as throwing acid on their merchandise or in their faces, having their shops and plants firebombed, or in some cases, having them murdered by Louis and Gurrah’s thugs. By May 1935 this group of gangsters included approximately 250 men, who did what Louis and Gurrah ordered and eliminated opponents and enemies when necessary.

These men and their thugs used force and fear to start gaining control of the garment industry unions. Louis’s control of the unions soon evolved into a protection racket, extending into areas such as bakery trucking. The unions were profitable for Louis and he maintained control over them even after he became an important man in organized crime. Louis later formed an alliance with Tommy Lucchese, a leader of the Lucchese crime family, and together they controlled the garment district.

Louis and Shapiro moved into new luxury apartment buildings on Eastern Parkway with their families who were active synagogue goers. They attended Union Temple and Kol Israel Synagogue of Brooklyn. Louis and his family later rented an elegant penthouse in the exclusive Central Park West section of Manhattan.

In 1927, Louis and Shapiro were arrested for the murder of Jacob Orgen (Little Augie), their former accomplice, and the attempted murder of Irish-American bootlegger named Jack Diamond who was a criminal rival. However, the charges were later dropped due to a lack of evidence.

Louis was known to generously compensate his gang members by treating them to hockey games and boxing matches. He even paid for them to take winter cruises. On August 20, 1931, Louis married Betty Wasserman, a British-born widow from Russia. Louis later adopted Betty's son, Harold from her previous marriage. Louis drove a large flashy black automobile, and took his family on trips to Europe and other pricey locales.

In November 1933, federal officials launched a huge legal case. In it, they indicted five labor organizations, 68 corporations, and 80 individuals for violating the Sherman antitrust law or conspiring to do so. The “worst” offenders charged were Louis and Gurrah, who were accused, along with others, of attempting to prevent fur dealers and manufacturers from conducting business through their bogus Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. For annual payments of $20,000, “L and G” promised “to protect the interests of the fur dressers against undue competition.” The case lasted for several years and it took until November 1936 to convict the two gangsters. But the two-year sentences and $10,000 fines permitted were a “mere slap on the wrist,” as the presiding judge remarked.

In the early 1930s, Louis created an effective process for performing contract killings for Cosa Nostra mobsters. It had no name, but a decade later, the press dubbed it “Murder, Inc.” Murder Inc. enlisted the best killers in the industry. It consisted of a ring of hitmen and Mob enforcers who are estimated to have murdered as many as 1,000 people in less than 10 years. Despite the name, though, Murder Inc. wasn’t just about killing. The gang would also threaten or maim people, depending on what their bosses wanted. These killers were brutal. They didn't just shoot their targets — they wanted to send a message. These gangsters hacked up the bodies of their victims with meat cleavers and ice picks. One man was set on fire. Another was strapped to a slot machine and left in public view. “Murder, Inc. was a business model that ended up making them very, very rich. It was essentially just a centralized system to coordinate contract “hits” by using gunmen, who were mostly Jewish and Italian gangsters—with no connection to those who were killed, thereby protecting the gangster head who had given the order for the murder.

Besides Louis, the leaders of Murder, Inc. were Abe “Kid Twist” Reles and Albert “The Mad Hatter” Anastasia, the infamous killer who was also called “Lord High Executioner.” The headquarters of the Jewish section of Murder, Inc. was located in Mrs. Rosie Gold’s shop called Midnight Rose Candy Store located in Brownsville. This Brooklyn storefront catered to children through the front door and killers through the back. Murder Inc. was established by Meyer Lansky and Benjamin "Bugsy" Siegel who were notorious gangsters and it was run by Louis. Of course, this all came out of the formation of the National Crime Syndicate, a group led by some of the most infamous mobsters of the era, including Charles "Lucky" Luciano, Lansky, Siegel, Frank Costello, Vincent Mangano, "Joe Adonis" Doto, Louis, and Shapiro.

Murder Inc.'s reign of terror continued until the early 1940s. The Murder, Inc., killers were soon completing jobs all over the country for their mobster bosses. By then, the gang's members were so bold that they'd pull off their murders in broad daylight, feeling certain that no one would ever try to stop them. Unfortunately, the gang made one critical mistake early on, an error named Abraham Reles. Abe Reles was not only willing to talk, but he also had a photographic memory and provided authorities with thousands of pages of evidence. Reles was extremely valuable to the police because Reles was a high-ranking member of Murder Inc. and also because he had a lot of information that could bring down other big names. With Reles’s help, the police located dozens of bodies and had enough evidence to lock up some of Rele’s friends and send several other friends straight to the electric chair.

The biggest mobster that Reles was able to offer the police was Albert Anastasia. The authorities previously had been unable to pin anything directly on Anastasia until they found out about Reles. Due to his value as a witness and the possibility that some of his old friends were likely trying to silence him from testifying against Anastasia, the NYPD placed Reles under continuous guard at the Half-Moon Hotel 1n Coney Island. Although 18 men were assigned to guard Reles in 24-hour shifts, on November 12th, 1941, the police discovered Reles’s diseased body on the sidewalk six stories down. Reles was found with “two sheets partially entwined around him” as well as a strip of wire. In his room, investigators found more wire tied to his radiator and leading out the window, where it had broken. The officers assigned to watch him all claimed that they had been asleep when Reles evidently decided to attempt an escape.

Anastasia played a part in the murder of a local teamster named Morris Diamond. Anastasia had dozens of hitmen (who Reles could have provided) to do the killing and assure he could never be directly blamed. However, for reasons that are unknown, Anastasia planned out Diamond’s death himself. Unbeknownst to Anastasia, Reles had overheard the details.

A key Murder, Inc., assassin was Harry “Pittsburgh Phil” Strauss, who murdered at least 100 men. Strauss was paid a salary of least $125 a week. His preferred weapons included guns, ice picks, and garrotes. Following an arrest and trial, Strauss was executed in Sing Sing’s electric chair in June 1941.

In 1935, Lewis Valentine, the New York City police commissioner, rightly described Louis “as among the nine most notorious and dangerous criminals” in the United States. In this year, Louis arranged his most significant murder: the powerful New York gangster Dutch Schultz. This was one of Murder, Inc.’s most memorable hits. Schultz had proposed to the National Crime Syndicate, a confederation of mobsters, that New York District Attorney Thomas Dewey be murdered. Co-founder of the Syndicate and leading mafioso Charles "Lucky" Luciano argued that a Dewey assassination would precipitate a massive law enforcement crackdown. An enraged Schultz said he would kill Dewey anyway and walked out of the meeting. After six hours of deliberations The Commission ordered Louis to eliminate Schultz. On October 23, 1935, Schultz was shot in a Newark, New Jersey tavern, and succumbed to his injuries the following day. In 1941, Louis’s killer Charles "The Bug" Workman was charged in the Schultz murder.

In 1935, law enforcement estimated that Louis and Shapiro had 250 men working for them, and that Louis was grossing over $1 million ($22,000,000 in current dollar terms) per year. They controlled rackets in the trucking, baking, and garment industries throughout New York. Louis also owned the Riobamba, a posh nightclub in Manhattan. Louis rarely raised his voice, yet their gang of sluggers, thugs, and killers, who called him “The Judge” or “Judge Louie,” feared him more than they did Gurrah. As one of their men, Sholem “Sol” Bernstein, put it: “I don’t ask questions, I just obey. It would be … healthier.”

Louis had a run in with a local New York small-time businessman named Joseph Rosen. Rosen, 46 years old, was murdered in September 1936, but his killing also proved to be Louis’s undoing. It was a fateful decision that ultimately ended Louis’s life, also. In the early 1930s, Rosen was a partner in a medium-size New York City clothing manufacturing company and also owned several trucks for the distribution of the goods. Refusing to fork over his hard-earned money to Louis and Shapiro, his machinery, including his trucks, was repeatedly vandalized and he was threatened on many occasions. Early in 1933, Rosen’s son Harold recalled witnessing a heated discussion between his father and the usually calm Louis. Harold later testified that Louis “pushed his face within six inches of my father’s face,” who returned to the office “white” and “shaken” from the intense conversation. Six months later, unable to withstand the threats, Rosen’s company went out of business. Trying to get back on his feet, Rosen eventually opened a small candy and newspaper store and started saving money with a plan to restart a garment trucking company.

In 1935, when New York Gov. Herbert Lehman appointed Thomas Dewey as a special prosecutor to investigate rackets and racketeers undermining New York’s various industries, a rumor circulated that Joseph Rosen was going to offer incriminating information about “L and G’s” criminal operations. Whether the rumor was true or not is unknown, though Dewey later denied that he knew Rosen or had spoken to him. A few weeks before Rosen was killed, Samuel Levine, a business agent and former president of a local clothing drivers’ union, urged Rosen to remain silent—Rosen never got a chance to do so.

It was later revealed by one of Louis’s former gunmen, Max Rubin—who survived an attempted assassination after Louis decided that Rubin was a liability—that Louis had ordered a “hit” on Rosen. On Sept. 13, 1936, as Rosen opened his shop in the early morning, three or four gangsters opened fire on him, shooting him 15 times and killing him. For several years, this murder went unsolved, until federal and state justice authorities came after Louis and Shapiro.

The Cosa Nostra mobsters wanted to insulate themselves from any connection to these murders. Louis’s partner, mobster Albert Anastasia, would relay a contract request from the Cosa Nostra to Louis. In turn, Louis would assign the job to Jewish and Italian street gang members from Brooklyn. None of these contract killers had any connections with the major crime families. If they were caught, they could not implicate their Cosa Nostra employers in the crimes. Louis used the same killers for his own murder contracts.

On September 13, 1936, Murder, Inc. killers, acting on Louis’s orders, gunned down Joseph Rosen, a Brooklyn candy store owner. Rosen was a former garment industry trucker whose union Louis took Rosen had angered Buchalter by refusing to leave town as Louis demanded when, despite the absence of proof, Louis believed Rosen was cooperating with District Attorney Thomas Dewey. At the time, no one was indicted in the Rosen murder. It was believed the Murder, Inc. killers dispatched 13 men to their graves during this period, including the candy storeowner Joseph Rosen.

In November 1933, federal officials launched a huge legal case. In it, they indicted five labor organizations, 68 corporations, and 80 individuals for violating the Sherman antitrust law or conspiring to do so. The “worst” offenders charged were Louis and Gurrah, who were accused, along with others, of attempting to prevent fur dealers and manufacturers from conducting business through their bogus Protective Fur Dressers Corporation. For annual payments of $20,000, “L and G” promised “to protect the interests of the fur dressers against undue competition.” The case lasted for several years and it took until November 1936 to convict the two gangsters. But the two-year sentences and $10,000 fines permitted were a “mere slap on the wrist,” as the presiding judge remarked.

On November 8, 1936, Louis and Shapiro were convicted of violating federal anti-trust laws in the rabbit fur industry in New York. While out on bail, both Louis and Shapiro disappeared. On November 13, both men were sentenced in absentia to two years in federal prison. The two men later appealed the verdict, but in June 1937 both convictions were upheld.

In August 1937, Louis and Shapiro were released on bail pending an appeal with an understanding that Dewey was about to indict them for conspiring to extort money from clothing manufacturers and baking and flour factory owners. Louis and Shapiro feared long prison sentences and thus went into hiding.

Before they could be taken into custody, both Louis and Shapiro disappeared. On November 9, 1937, the federal government offered a $5,000 reward for information leading to Louis’s capture. Despite substantial rewards for information about them, the police could not locate either man. It was speculated in the press that Louis had fled to Poland or Palestine. However, for two years, Louis never left New York City. He gained weight and grew a mustache to disguise himself and hid out in apartments and rooms in Coney Island and other parts of Brooklyn. Presidentially ambitious District Attorney Thomas Edmund Dewey branded Louis as “probably the most dangerous criminal in the U. S.” and posted a $25,000 reward for his capture dead or alive.

Shapiro became tired of running and hiding from the police. Therefore, he surrendered in April 1938 and was sent to prison to serve a two-year sentence. Shapiro was soon additionally convicted of extortion and conspiracy and received an additional 15-year sentence. Shapiro died of a heart attack in prison in June 1948.

Louis stayed hidden until August 1939. Using the syndicated newspaper columnist Walter Winchell as an intermediary, Louis gave himself up to J. Edgar Hoover, the head of the FBI. Within a few months, he was indicted by federal justice authorities for his part in a massive narcotic smuggling operation. It was alleged that from 1935 to 1937, $10 million worth of narcotics (presumably heroin and cocaine) were transported to the U.S. from Shanghai via Cherbourg and Marseille in France. Several customs agents, who had been paid off and had enabled the shipments to pass easily into the country, were also charged. At the end of 1939, Louis received a 14-year sentence on the procurement and sale of narcotics and was sent to the federal penitentiary in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Meanwhile, William O’Dwyer, who was elected district attorney of Brooklyn and later served as the mayor of New York City from 1946 to 1950—was determined to end corruption and racketeering and take down the murder syndicate. Owing to information provided by Max Rubin and Abe Reles, who after being indicted for murder tried to save himself by becoming a government informant (he later mysteriously died by falling out of a window while the police were guarding him), O’Dwyer had sufficient evidence to charge Louis and two of his men with the 1936 murder of Joseph Rosen. In May 1940, the one issue stopping O’Dwyer from proceeding immediately with the case was the intransigence of the federal justice authorities and their jurisdictional power over Louis. Months of negotiations followed and finally in mid-May 1941, Louis was transferred from Leavenworth to the Kings County Courthouse in Brooklyn to be arraigned on the murder charge. According to reporters present in the courtroom, Louis was “visibly nervous with a tremor in his voice.”

On December 1, 1937, the fugitive Louis was indicted in federal court on conspiracy to smuggle heroin into the United States. The scheme involved heroin hidden in the trunks of young women and couples traveling by ocean liner from China to France, then to New York City. Louis bribed U.S. customs agents not to inspect the trunks.

On August 20, 1940, Louis was indicted on murder charges in Los Angeles for the killing of Harry Greenberg, a mob associate of casino owner Meyer Lansky and mobster Bugsy Siegel. However, Louis never went to trial on this killing.

After Louis was convicted on the federal narcotics trafficking charges, federal authorities turned him over to New York State for trial on labor extortion charges. On April 5, 1940, Louis was sentenced to 30 years to life in state prison on those charges. However, Louis was sent to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary in Kansas to serve his federal sentence of 14 years for narcotics trafficking.

On May 9, 1941, Louis was arraigned in New York state court on the 1936 Rosen murder along with three other murders. Louis’s order for the Rosen hit had been overheard by mobster Abe Reles, who turned state's evidence in 1940 and implicated Louis in four murders. Returned from Leavenworth to Brooklyn to stand trial for the Rosen slaying, Louis’s position was worsened by the testimony of Albert "Tick-Tock" Tannenbaum. Four hours into deliberation, at 2 am on November 30, 1941, the jury found Louis guilty of first-degree murder. On December 2, 1941, Louis was sentenced to death along with his lieutenants Emanuel "Mendy" Weiss and Louis Capone. Buchalter's lawyers immediately filed an appeal.

In October 1942, the New York Court of Appeals voted four to three to uphold Louis’s conviction and death sentence. Two dissenting judges thought the evidence was so weak that errors in the jury instructions as to how to evaluate certain testimony were harmful enough to require a new trial. The third dissenter agreed, but added that, in his opinion, there was insufficient evidence to sustain a guilty verdict, so the indictment should be dismissed altogether (failure of proof means no retrial). Louis’s lawyers then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The United States Supreme Court granted Louis’s petition to review the case. In 1943, the Court affirmed Louis’s conviction seven to zero, with two justices abstaining. His appeals were now exhausted.

The last attempt to delay the execution came from an unlikely source. Rabbi Jacob Katz was the Jewish chaplain at the prison and served as Louis and Weiss’s spiritual advisor. Executions at the prison traditionally took place on Thursday nights at 11 p.m. Katz telephoned the governor Saturday morning, asking him to not conduct the executions that evening because it was the Jewish Sabbath. Due to holding services on the Sabbath, Katz said he could not leave his responsibilities in the Bronx until sundown, which would only give him "a scant three hours" with his two charges. This request was denied.

When the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed Louis’s conviction, he was serving his racketeering sentence at Leavenworth Federal Prison. New York State authorities demanded that the federal government turn over Louis for execution. On January 21, 1944, after many delays and much controversy, federal agents finally turned Louis over to state authorities, who immediately transported him to Sing Sing prison. Louis made several pleas for mercy, but they were rejected.

The condemned men were shaved. Then they showered, and were dressed in the traditional death-night garb of white socks, carpet slippers, and black trousers with a slit in one leg so the electrode could be attached to the bare skin. From the pre-execution chamber the men were just 25 feet from the chair. Set apart by partitions, the prisoners could not see one another but could communicate. Given the traditional choice of selecting their last meals, Louis had requested steak, French fries, salad, and pie for lunch; and for dinner – roast chicken, shoestring potatoes, and salad. Weiss and Capone, as always following the boss’s lead, ordered the same.

Having had their last meals for the second time in three days, the trio realized when no word from the governor’s mansion was received by 10:45 p.m. that all hope was lost. With the witness room packed with 36 on-lookers, Louis Capone was the first to be executed.

Louis quickly walked in with Rabbi Katz. His step was described as brisk and defiant. He almost threw himself into the chair. On March 4, 1944, Louis Buchalter was executed in the electric chair in Sing Sing. He had no final words. However, Mrs. Beatrice Wasserman Buchalter, Lepke’s wife stated, "My husband just dictated this statement in his death cell. I wrote it down, word for word." Frank Coniff, a reporter for the New York Journal American, was one of the witnesses. He wrote, "You look at the face…you cannot tear your eyes away. Sweat beads his forehead. Saliva drools from the corner of his lips. The face is discolored. It is not a pretty sight."

"I am anxious to have it clearly understood that I did not offer to talk and give information in exchange for any promise of commutation of my death sentence. I did not ask for that!" (The exclamation point was Louis’s.) "The one and only thing I have asked for is to have a commission appointed to examine the facts. If that examination does not show that I am not guilty, I am willing to go to the chair, regardless of what information I have given or can give."

In Burton Turkus’s book, Murder, Inc. he claims: "By releasing the statement through his wife, Louis also was, I am convinced, giving an unmistakable signal to the mob. He was broadcasting to his Syndicate associates that he had not and would not talk of them or of the national cartel. About politicians and political connections and the like – yes: the crime magnates would seek no reprisal for that. But not about the top bosses of crime. It was pure and simple life insurance. No member of his family would be safe if the crime chiefs believed he had opened up on the organization itself."

Louis Buchalter was buried at the Mount Hebron Cemetery in Flushing, Queens.